Rise of the Robots: Well and Truly This Time?

29th August 2020

“We’re robots made of robots made of robots.” – Daniel C. Dennett, philosopher and cognitive scientist.

The robots are coming, finally. That seems to be the message from several futurists and other types of forecaster as the novel coronavirus continues to shatter the economic certainties of only a few months ago.

Among the latest developments in the embrace of robots in 2020, Boston University and other US campuses are using platoons of robots to keep students and staff safe as campuses reopen. Governments and social organisations around the globe are promoting the use of robots to manage loneliness among demographic groups such as the elderly and the sick. And, more controversially, companies across the developed world have begin replacing some workers with robots in order to manage the risks of the pandemic in the workplace and boost local manufacturing in response to geopolitical tensions. In China, the centre of the world’s manufacturing industry and a key driver of relatively cheap robots for a range of tasks, investors are pouring money into robotics.

What accounts for the rising prospect of a widespread adoption of robots in the medium to long term? The salient points have become evident to most of us in recent months:

- Robots do not get sick.

- Robots do not need to ‘social distance’ or stay home in lockdowns.

- Adopting robots more widely in manufacturing will permit many workforce-challenged nations to recover the ability to make things – a shortcoming that the pandemic has very painfully revealed.

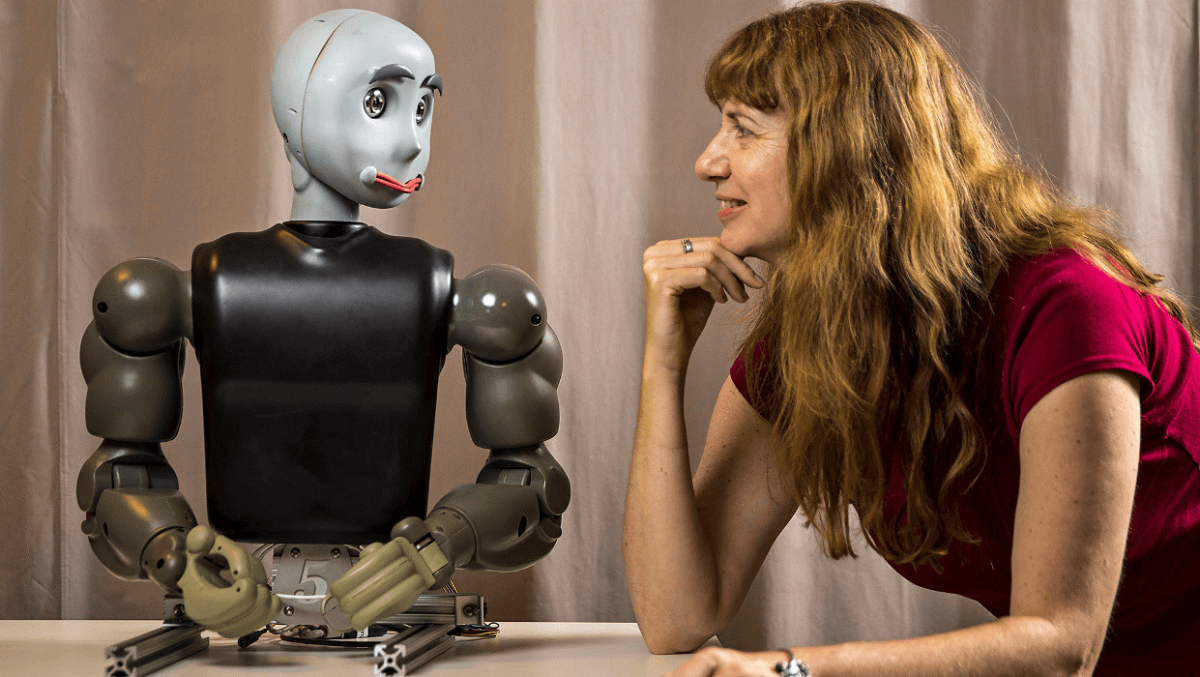

And it is not just the more general-purpose and visually arresting advanced robots (such as Boston Dynamics’ famous Spot in the picture above) that are going to be seen around us soon. Robots designed to perform specialised tasks at everyday places are likely to gain wider acceptance. To quote Mark Muro of the Brookings Institution: “When you have the effect of social distancing and infection, it adds to the rationale for the substitution of machines for humans at point-of-sale positions like a cashier for food service, or in hospitals.” In several Asian countries, as well as in the US and Europe, robots are already helping disinfect hospitals, keeping their electronic eyes steadily trained on patients’ vital readings, and delivering lifesaving drugs speedily and safely. Senior executives at even small-to-medium robotics firms such as Soft Robotics and Fetch Robotics have reported a surge in demand from manufacturers and supply chain companies, which have been struck by locked-down workforces. In one parallel trend of especial relevance to Australia’s sprawling agriculture sector, which is perennially struggling to find harvest workers, prototype robots from Fieldwork Robotics are already harvesting crops in parts of the UK. However, despite the growing optimism in automation circles, some experts (including authors of a piece on HBR.org), have argued that, for now at least, robots only appear to be truly useful when the environment they work in is controllable, and the work that they do comprises bottleneck tasks.

An acceleration in robotics and AI around the corner? Visionary tech tycoon Elon Musk claimed in July 2020 that humans may be overtaken by artificial intelligence by 2025, but others are more cautious.

There are clear risks, of course – the most prominent being social. In an era of large-scale job losses, bringing in robots to replace low-income jobs could cause social ructions. As Carl Benedikt Frey of Oxford University pointed out recently, automation and digital technologies were seen as potential sources of social unrest even before the pandemic, so any further inroads into the workforce by robots could only cause this risk to rise. Assurances by corporations and companies that robots will augment human workers and not replace them are unlikely to assuage these anxieties. This unease reared its head at Amazon not too long ago, when first responders arriving to fix a gas leak at a warehouse struggled to navigate past many robots scampering about the vast building.

Robotics expert Maja Matarić of the University of Southern California has told National Geographic: ‘The people who take care of other people … are underpaid and underappreciated. Until that changes, using robots is what we’ll have to do.’

What could mitigate this risk of turmoil caused by the fear of robots as potential job-thieves? One measure rolled out in various guises by governments around the world since mid-March may save the day: a universal basic income (UBI). Former US presidential candidate Andrew Yang and British economist Guy Standing, among others, are prominent proponents of UBI. In Australia and the UK, the current pandemic-driven economic crisis has resulted in UBI in the form of ‘JobKeeper’ and ‘Furlough,’ respectively. While this is meant to be a temporary measure, it may well turn out to be a harbinger of a more permanent intervention.

While time only will reveal where we land on the robotics front, we at MyTreasur-e are already sure of one unshakable truth: our customers need the best treasury management system, supported by utterly reliable service. And, whether or not robots pop up everywhere in coming months, our cutting-edge treasury management solution will always be there for you.